United-Real 2000: the end of an aura

One side had Beckham, Keane, Scholes, Giggs – but the other had Raul and Redondo. The full story of a clash of the titans that became a game-changer for Alex Ferguson

19 April 2000, Champions League: United 2, Real Madrid 3 (agg: 2-3)

A football match lasts much longer than 90 minutes. It begins before the first whistle and continues beyond the final whistle. Every game has a back-story and a front-story, and matches exist in what the academic film critic Stephen Heath called an ‘englobingly extensive prolongation’. Few have had such an extensive prolongation as the immense Champions League quarter-final between Real Madrid and Manchester United in 2000 when Real, having drawn the first leg 0-0, won 3-2 at Old Trafford in a game notable for the staggering quality its of attacking play and a famous tactical switch from Vicente del Bosque.

In a sense the tie began 40 years earlier, when a teenage Alex Ferguson sneaked into Hampden Park and was spellbound by Madrid’s 7-3 evisceration of Eintracht Frankfurt in the European Cup final. And it continued to reverberate until Ferguson’s last Champions League game against, yep, Madrid in 2013. Every time United lined up for a big game at home or in Europe under Ferguson, their tactics were a direct consequence of that chastening experience against Madrid. Del Bosque spoke of United’s 'tactical anarchy' that night, and Ferguson ensured such suggestions could never be made again. Until that game his teams tried to score one more than the opposition; afterwards they tried to concede one fewer.

Real’s win ended United’s reign as European champions, at a time when many felt Ferguson’s young side were going to establish a dynasty, and instantly restored their own faded glamour. It also changed Del Bosque’s life. Until then he had been Real’s odd-job man, almost a Spanish Tony Parkes, but that match set him on the road to becoming one of the most successful coaches of the early 21st century. All of that, and Ferguson’s tactical epiphany, mean that this was arguably the most epochal European match since Heysel, although for very different reasons. Del Bosque's tactical brainwave caused shockwaves that changed the landscape of modern football.

The contest was so multi-faceted and multi-layered that, almost uniquely, it defied received wisdom. For every two people who say that Real taught United a lesson, there is another pointing to the stream of chances that United created. The match was deliciously inscrutable. It was certainly superior to the sequel in 2003, a wildly entertaining but largely meaningless contest that United won 4-3. The fact that United had lost the first leg 3-1 meant that, once they conceded an early goal at Old Trafford, they were never seriously in contention to go through. It was a glorified exhibition match.

The same could not be said of the meeting three years and four days earlier, which crackled with intensity even when United needed four goals in half an hour to qualify for the semi-finals. They had abnormal levels of self-belief, having accomplished so many missions impossible over the previous 18 months, but as the result marinated, so that self-belief began to seep away. Something died in the United team that night. And something certainly died in Ferguson: his faith in the power of swash and buckle.

It is easy to forget the extent to which Madrid were underdogs. United, the reigning European champions, were romping away with the Premier League: they led by 10 points with seven games to play, would eventually win by 18, and their final total of 97 league goals was the highest in the English top flight since 1964. On the Saturday before their trip to Spain they went 1-0 down to West Ham and responded by scoring seven.

Madrid, by contrast, needed seven exceptional saves from their teenage goalkeeper Iker Casillas to earn a 1-1 draw at Real Sociedad. Not that even Casillas’s heroism was cause for celebration: the draw all but ended Madrid’s feeble title challenge.

They were having a diabolical season, and ended up finishing fifth in the league. John Toshack had been sacked in November with Madrid slumming it in 16th. His replacement, Del Bosque, who had already had two spells as caretaker coach in 1994 and 1996, was only put in charge until the end of the season. In his second home league game, Madrid were thrashed 5-1 by Zaragoza. Later they were thumped 5-2 by Deportivo La Coruña, and in the second Champions League group stage they lost 4-2 and 4-1 to Bayern Munich. They only qualified for the quarter-finals because of a superior head-to-head record against Dynamo Kyiv. Had goal difference been the decider, Madrid would have gone out.

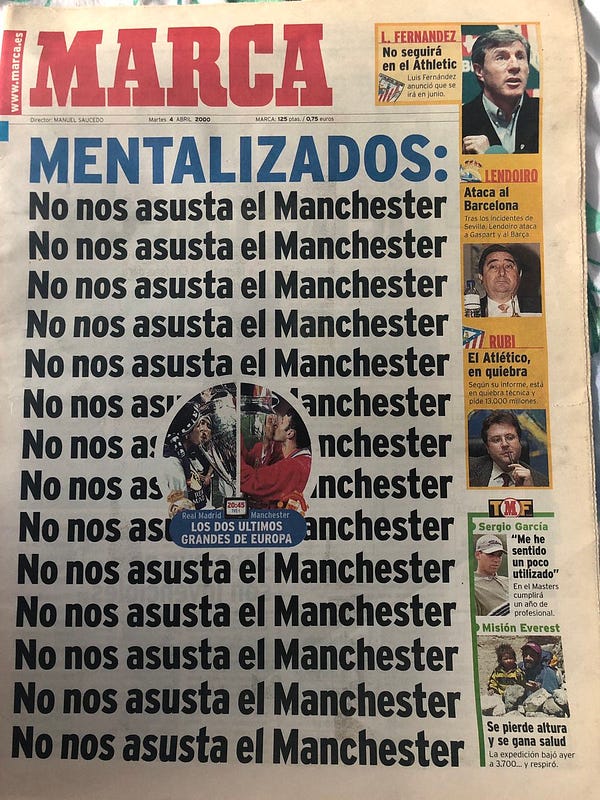

On the day of the United match, Marca devoted its entire cover to one phrase, repeated 14 times: 'No nos asusta el Manchester' ('Manchester don’t scare us'). You did not need an NVQ in psychology to know what was going on.

In the Independent, the Spanish football expert John Carlin dismissed their chances. 'If team spirit, if individual skill, if organisational solidity, if current form are the elements that determine the outcomes of football matches, there is no way Real Madrid can knock Manchester United out of the European Cup,' he wrote. 'So overwhelming is United’s superiority in almost every department that, should Real win, those who make a living out of imposing conventional reason on the beautiful game (football writers, say, or television pundits) will be obliged to concede that they are trading in gibberish, that analysis counts for nothing, that victory and defeat in football are determined by forces that surpass human understanding.'

Carlin was far from alone in drawing such a conclusion. In the aftermath of that astonishing victory over Bayern Munich, it was widely assumed United would dominate Europe for the next five years and establish the same kind of legacy as the great Bayern, Ajax and Liverpool sides of the 70s and 80s. The main reason for that was United’s almost unprecedented sense of omnipotence. It wasn’t necessarily arrogance; they conceded the first goal far too often to think they were bullet-proof, but they came back so consistently that there was an understandable if misplaced feeling that they could get out of any hole. In the 21 months since the start of the 1998-99 season, when the signing of Jaap Stam and Dwight Yorke completed the construction of this particular side, they had come from behind to win or draw 31 games, eight of them in Europe, two of them, against Juventus and Bayern the previous season, in circumstances that beggared belief. 'I don’t think this team ever loses,' said the assistant coach Steve McClaren. 'It just runs out of time.'

Their rare defeats could be rationalised in other ways. Their failure at the Club World Championship in Brazil could be attributed to an alien environment and a once-in-a-lifetime shocker from Gary Neville, who got the yips and gifted Romário the first two goals in a 3-1 defeat to Vasco da Gama. Of United’s three league defeats in the previous 16 months, two had come when they were down to 10 men for large parts of the game, at Chelsea and Newcastle, and the other, a 3-1 loss at Spurs, involved three freakish goals. There was an unspoken sense that, with a level playing field, United could not be beaten. They certainly had few fears about Real. 'We weren’t going to underestimate them,' wrote Jaap Stam in his autobiography, 'but there was a feeling around the squad that the draw could have been a lot trickier.'

‘Redondo’s primary job was to carry water, albeit more gracefully than most, but at Old Trafford he walked on it’

Life has never been as good as it was for United on the afternoon on 4 April 2000 as they approached the kick off in the first leg. Even when they reached three Champions League finals in four years from 2008-11, their aura was not as powerful. 'If the club lives for another thousand years, men will look back and say, ‘This, then, was the drunkest hour’,' wrote the United fan Richard Kurt in the Irish Examiner on the day of the Madrid game. 'At this moment, as the red clans clamorously gather, the universe seems ours for the taking.'

A year earlier, United had lived on the edge throughout their triumphant European Cup campaign. Even their spectacular victory over Juventus came after they’d been 2-0 down. Now, it seemed, they had the chance to take the next step by hammering Real on their own patch. Instead, a peculiarly passive United were fortunate to earn a 0-0 draw.

Although Real had much the better of the game, United had the best chance, with Andy Cole heading over from three yards after Stam had flicked on David Beckham’s corner. Glenn Hoddle famously said that Cole needed five chances to score and, while most were happy to treat the word of Hod as gospel in this instance, the reality is that Cole’s problem was not the quantity of his misses but the nature of them. There were some shockers throughout his career, which meant that Cole, arguably the most rounded England striker of his generation, was often treated as a bit of a joke. Take this Madrid tie: Cole is remembered for missing that chance, yet he contributed appreciably more than the largely anonymous Dwight Yorke.

Yorke did have a tap-in disallowed for offside on the stroke of half-time after an unsighted Casillas failed to hold Paul Scholes’s stinging shot. Replays were not conclusive, although it appeared Yorke was just being played onside by Roberto Carlos’s trailing leg.

That potential injustice did not alter the fact that Madrid should have won the game. Only three United players really turned up: Roy Keane, who put out fires all across the field with his usual diligence and focus; Mark Bosnich, who made a number of good saves and two exceptional ones from Fernando Morientes and Steve McManaman; and Ryan Giggs, whose sporadic penetrative runs from an inside-left position hinted at the chasing he would give Real in the first half at Old Trafford.

'In the first game,' said the substitute goalkeeper Raimond van der Gouw, 'we had too much respect for the name Real Madrid.' The widespread perception is that Ferguson, in awe of Real Madrid ever since that trip to Hampden Park in 1960, sent his side out to play cautiously, yet he was critical of his players’ inability to seize the moment. 'He was sincerely dismayed by the drop in standards we had witnessed: the mental and physical sluggishness that allowed Real long periods of comfortable possession, the basic flaws in ball control and passing, the failure to match the fluency of the opposition's movement,' wrote Hugh McIlvanney, ghostwriter of Ferguson’s autobiography and his main press-box confidante, the following Sunday. 'But his hard words are better understood in the context of his pre-match feelings. “I was looking forward to the meeting with Real Madrid and wanted to use it as a platform to let everybody know Manchester United are the best in the game,” he told me later in the week. “Real are the team with the greatest record in the European Cup and we were facing them on their own midden. I was disappointed, and so were the players, that we didn't take the opportunity to show our true worth.”'

Either Ferguson or many of his players bottled it. It’s hard to be certain, but the adventure of the full-backs is often the most illuminating window into a side’s tactics. Denis Irwin and Gary Neville, usually so enterprising, barely crossed an imaginary line two thirds of the way up the pitch. The contrast with Real, whose 4-4-1-1 formation was ostensibly the same as United’s, was enormous: Roberto Carlos and Míchel Salgado were a constant attacking influence.United’s tactics were like greeting a dangerous but woefully out-of-form batsman with one slip and a maan in the deep on both sides.

It was in total contrast to their approach to away games in 1998-99 — although it should be noted that, in three of their four main matches, against Bayern Munich, Barcelona and Juventus, they conceded in the first 11 minutes and were thus compelled to attack. As a rule, however, Ferguson was happy to take risks at the back. When he paid a record fee for Stam in 1998, one of the principal reasons he cited was Stam’s ability to defend in one-on-one situations.

The 0-0 scoreline stirred uncomfortable memories for United, who had gone out of Europe on away goals in 1995-96 and 1997-98 after a similar first-leg score, yet the bookies made them 2-5 favourites to progress. After all, they only needed to win a football match at home, something they had managed in 29 out of 35 games since their last home defeat, to Middlesbrough in December 1998. The problem was not with the scoreline but the manner of the draw. In playing so meekly, United allowed Madrid to rediscover their confidence.

'A lot of people on our side of the fence thought 0-0 was a good result but I was disappointed and worried,' Ferguson said in his autobiography. 'Maybe I was a bit like the farmer who can divine the weather in his bones, getting pains and funny feelings when the rain is coming.’

In the two weeks before the second leg, United beat Middlesbrough 4-3 and Sunderland 4-0, while Madrid won 1-0 against Celta Vigo and Real Zaragoza. But it no longer mattered how many goals United scored domestically; far more relevant, for Madrid, was the evidence of the first leg. There was no need for a special Marca cover on the day of the second leg. Manchester no longer scared them.

The introduction of the second group stage meant that the quarter-finals were played over a month later than they had been the previous season, and much of the first half of the second leg was played in daylight. The only change to either side from the first leg was the replacement of the injured Bosnich by van der Gouw. But Real’s side took on a completely different shape, an unprecedented and unbalanced 3-3-2-2 formation that caught everyone by surprise — including the newspapers, the majority of which were still calling it a 4-4-2 the following morning. Under Del Bosque, Madrid had never played with three centre-backs before; to do so in this of all games was an audacious and brilliant conceit.

Iván Helguera dropped back from midfield to be the spare man at the back, allowing Roberto Carlos and Salgado to do what they did best: attack. McManaman roamed from the right of centre, as did Sávio from a more advanced inside-left position. That left Madrid with just one orthodox central midfielder: the imperious Fernando Redondo, who was about to have the game of his life. Many United veterans still talk of this as the greatest individual performance by an opposing player at Old Trafford, just ahead of Dejan Savićević’s languid masterclass for Red Star Belgrade in 1991.

Without Redondo, Madrid would have been the ones guilty of tactical anarchy. 'They were playing a system that did not deserve to be successful,' said Ferguson. 'One central midfielder. “Give us a break,” I thought to myself. “That can’t work’”' One thing that did not surprise Ferguson was Madrid’s aggressive start to the game, which he had predicted in his pre-match press conference. In the second minute, Roberto Carlos worked a smart overlap with Sávio before running at Beckham and smashing a low, angled cross into the corridor of uncertainty between defenders and goalkeeper. It just evaded Raúl, but the nervousness around the ground was palpable, an inevitable consequence of United conceding early goals at home to Borussia Dortmund and Monaco in their previous two exits from the Champions League.

'Some have suggested that Madrid outclassed us at Old Trafford, but I'm not having that’

The fear of the away goal and the form of Roberto Carlos were the defining features of the first 20 minutes. This was him at his very best, a carpe diem philosophy of a footballer imposing his skill and athleticism on his direct opponents. After the first leg, he had announced that Beckham was 'one-footed, lacking pace and unable to go past people'. If you go at the Prince, you’d better not miss. While the last bit looked a little daft when Beckham scored a thrilling solo goal later in the match, the assessment was essentially a fair one. And Roberto Carlos backed it up by wiping the floor with both Beckham and Neville for most of the second leg.

When Neville mistimed his jump at a long, angled pass from the back by Helguera, Roberto Carlos surged into the area before playing the ball square for Morientes, whose 15-yard shot was just too close to van der Gouw. It was a desperate and unusual mistake by Neville, who was in the midst of the only extended slump of his career, yet to regain his confidence after that Romário nightmare three months earlier.

Although there had been a couple of scintillating runs from Giggs, Real were unexpectedly dominant and had 55 per cent of possession in the first 15 minutes. Neville made another mistake in the 17th minute, underhitting a square pass to his goalkeeper that was seized on by — inevitably — Roberto Carlos. Van der Gouw flew from his line and managed to block his shot, but United’s nervousness was palpable. 'We were too slow to adjust [to Madrid’s formation],' said Ferguson. 'I thought about changing my own system. To our cost, I delayed too long. If I had altered the team early to a 4-3-3, playing two men wide and one central striker, I am sure we could have won handily. I know that, and could kick myself for delaying the change. With three midfielders, we would have been able to get against Redondo as a priority and would have handled Raúl better when he dropped into midfield from his normal front position.'

Ferguson was often slow to react in terms of tactical changes, a surprising flaw given his ability to make difficult decisions in almost every other aspect of his job. In this instance, however, his passivity was reinforced by the fact that the scenario was so familiar. United almost always started slowly, and almost always got the result they needed. They had that incredible record of coming from behind to win or draw 31 games since the start of the 1998-99 season; and in their previous home European game, they had gone behind to a howitzer from Gabriel Batistuta before recovering to pummel Fiorentina much more emphatically than a 3-1 scoreline suggested.

Ferguson’s stock phrases were that 'we always do it the hard way' and 'it’s the nature of our club'. It was as if United needed to go behind to get themselves going. With hindsight it seems reductive to indulge such weakness, but at the time it seemed like a charming eccentricity of a brilliant side - a foible rather than a flaw. 'Going behind doesn’t faze the players,' he said. 'They’ve got the patience, resolve and endurance to get back from situations like that.' The 3-2 win in Juventus was a flawless example of the controlled aggression needed to overcome an apparently lost cause.

On the day before the game, Ferguson seemed almost amused by his side’s vulnerability. 'It’s just the make-up of our club,' he said. 'I keep saying to the players, ‘Let’s get over the first 20 minutes.’ When did Batistuta score? 19 minutes [it was actually 16]. So we’re getting there!' They so nearly got there against Madrid. And then, after 19 minutes 31 seconds, Real Madrid took the lead through the most improbable source: Roy Keane.

The goal stemmed from a United attack, and demonstrated the importance of butterfly effects in football. Scholes had made a typical late run and almost got on the end of Irwin’s fierce low cross; when Real broke he was out of the game, which meant Giggs had to come across into the centre to cover, leaving a gap out wide that allowed Real to work an overlap.

Helguera’s clearance came to Sávio, who gained 50 yards via a simple exchange of passes with Redondo and then moved the ball infield to McManaman. He was clattered from behind by Scholes in the act of moving it right to Morientes, who had Salgado overlapping. Morientes played the ball down the line for Salgado to pass a first-time cross towards the near post. It was going straight into the arms of van der Gouw, but Keane, unsure what was behind him, stretched out his left foot and diverted the ball into the net.

It was the most perverse plot twist. Keane seemed invincible at the time, and won both Player of the Year awards that season. His value to United had never been greater. He was 28 years old, right in his prime; it seemed like he could do anything. For that one season he even recaptured his youth by scoring 12 goals, the only time he reached double figures in his entire career. It would take him five years – his last five years at United – to manage another 12.

Earlier in the season, with his contract due to expire in the summer and United loath to break their wage structure, there was a serious chance that he would join Juventus or Bayern Munich. At Old Trafford, the prospect engendered a sense of terror, such was the essential inability of even this exceptionally talented team to function without Keane. The issue was not resolved until, just 24 days before he would have been entitled to negotiate a Bosman transfer abroad, he signed a new contract on the afternoon of the match against Valencia. Inevitably, Keane slammed in the opening goal that night in a 3-0 win.

Four months on, he again scored the opening goal against Spanish opposition. It was not his first high-profile mistake of the competition — a blind backpass had allowed Batistuta to open the scoring in Florence during the second group stage — and in the context of his otherwise incessant excellence, it was impossible to comprehend. Keane lay on his back for a couple of seconds, motionless and expressionless, before bouncing to his feet, intent on righting the wrong.

United’s response was emphatic and thrilling. In the next 20 minutes they created six clear chances with attacking football of irresistible verve and class. 'Keane was the dynamic force behind United's purple patch in the first half,' wrote Patrick Barclay in the Sunday Telegraph, 'when their football was as swift and deft as anything I have seen from them.'

The first chance came in the 22nd minute. Giggs collected the ball by the touchline 15 yards inside his own half, took four players out of the game with a dazzling run, and then played the ball to Cole on the left. He ran at Ivan Campo before curving a precise, deep cross to Yorke, who had pulled away from Aitor Karanka at the far post. There were shades of the equaliser in Juventus a year earlier, when Cole’s majestic cross was headed emphatically into the corner by Yorke. This time Yorke’s header was too close to Casillas, who was able to palm it away.

The ease with which Giggs was dribbling past Madrid players was a reflection of the fact that he was right on top of the game. There was another way of telling when Giggs was on song: when his beloved fancy flicks came off. In this match — and particularly in the first hour — there were loads of them.

One such flick created a great chance for Beckham in the 26th minute. For most of the game Beckham was stuck to the right flank, buried deep in Roberto Carlos’s pocket, but in this attack he wandered over to the left in open play and almost equalised. When Beckham’s ball forward deflected up in the air off Raúl, it was headed infield by Irwin towards Giggs, 25 yards out and with his back to goal. He flicked it around the corner on the half-volley to Scholes, who played a delightful first-time through pass, also on the half-volley, towards the onrushing Beckham. He was at a tight angle, seven yards from goal, and his left-foot shot hit the immaculately positioned Casillas on the shoulder.

By that stage, an equaliser seemed not so much in the post as sent by recorded delivery. Giggs turned majestically past Campo in the box with another of his flicks, but then fractionally overhit his chipped cross. Seconds later, Yorke headed a half-chance miles wide.

Then in the 29th minute, came a chance for Keane. In the first leg his role had been almost exclusively defensive, but in the first half hour at Old Trafford he got forward more than Scholes. Irwin’s perceptive low pass from the left was glanced expertly behind his standing leg by Cole on the edge of the box; Keane burst imperiously onto it, past Helguera and through on Casillas. He tried to go across goal with his left foot, but the shot deflected off the lunging Karanka and changed direction sharply. Casillas, already moving to his left, thrust up his right hand to make an awesome reaction save, the best of many he would make in this match.

'The keeper was marvellous but it's not normal for an 18-year-old to be like that,' said Ferguson. 'Not at all normal.' Then again, it was already apparent that Casillas was not normal. He had usurped Bodo Illgner and Albano Bizzarri, and before the first leg there had been that phenomenal display against Sociedad. 'You had to see it to believe it,' said John Toshack, who gave Casillas his debut. Toshack also called Casillas 'the most important player in the team'.

Although United were creating chances at will in that period, they still looked jittery when Real attacked. After a fine run from the impish Sávio, Roberto Carlos thrashed a free-kick wide from the edge of the D. In truth, United had been ropey at the back all season. Gary Neville was out of form, Mikaël Silvestre was out of his depth at that stage of his development, and Ronny Johnsen had not played all season because of injury. United conceded 45 goals in the league, their highest total between 1990-91 and 2018-19. But nobody really minded that the defence was so vulnerable, because the attack usually got them out of trouble.

That attack continued to create chances against Madrid. Irwin went on an improbable surge down the centre of the field and found Yorke. He slipped Helguera cleverly but then badly overhit a routine return pass to Irwin, who was through on goal. For a player of Yorke’s class, it was a diabolical error, and the usually undemonstrative Irwin threw his hands up in the air in disgust.

There were plenty of hands in the air a few minutes later: first those of Karanka, who flicked Cole’s goalbound header over his own bar with his left hand, and then Cole and Henning Berg, appealing desperately for a penalty. Casillas, whose one weakness in this match was in dealing with crosses, something that United did not exploit anywhere near enough, came for a deep Beckham corner and missed it. Yorke headed it back across goal, and Cole had an almost identical chance to the one he had missed at the Bernabéu. His header was going in until it flicked the fingertips of Karanka and looped onto the top of the net. It was a very hard decision for Pierluigi Collina — there were a mass of bodies, and the ball hit Cole’s head and Karanka’s hand almost simultaneously but it should have been a penalty and a red card. It was a huge if understandable injustice, yet very little was said about it after the match, either by United or in the press.

Not even United could maintain such asphyxiating pressure and, in a game of compelling fluctuations, Real almost extended their lead twice just before half-time. First Stam, off balance, diverted Salgado’s low cross straight to Raúl, who stabbed over with his right foot from 12 yards. Then, in injury time, McManaman’s right-wing cross deflected off Stam and onto the roof of the net with van der Gouw back-pedalling desperately. Had it dipped under the bar, he would not have got there.

McManaman, who had endured a modest first season at Madrid, excelled in both legs. He was booed furiously throughout at Old Trafford. This was not token hate for an ex-Liverpool player; Jamie Redknapp, for example, would not have invited anywhere near this level of opprobrium. United fans detested McManaman and Robbie Fowler because, as well as being Liverpool players, they were Scousers both by birth and by nature. McManaman wasn’t a huge fan of United either, and the glee he took from Madrid’s triumph was considerable.

His considerable influence challenges the lazy perception of continental sophisticates outsmarting British and Irish dunderheads. Real were slick and clinical on the counter-attack, and McManaman was a huge part of that. They might not quite have taught United a lesson in this match, as some felt, but that does not mean United didn’t learn anything. 'This was the standard we had to aim for, world class,' Keane said. 'A number of features of Real’s play struck me. The incredible first touch. The economy of movement, no daft running, every move purposeful. Raúl’s cunning, waiting like a panther to pounce on any half-chance. And burying it when it came.'

That was exactly what he did with a glorious goal in the 50th minute. It was the start of a seismic 138-second period in which Raúl scored twice and Keane missed an open goal. The general perception is that United, panicking because of the need for at least two goals, came out like headless chickens after half-time and were picked off. The reality was a little different. For the first few minutes after half-time, United were largely on the defensive, feeling their way into the second half. But then they won a free-kick on the right, 40 yards from goal, and lost their heads completely. Only the taker, Beckham, and Silvestre — on as a half-time substitute for Irwin, who had a hamstring injury — were behind the ball as the free-kick was taken. When the ball was eventually cleared, Salgado’s header fell nicely for McManaman, and from nowhere Madrid had a three-on-two break.

McManaman ran beyond the halfway line and then played a beautiful left-footed pass over Silvestre for the lurking Raúl, 45 yards from goal in an inside-right position. His first touch was superb, a cushioned flick with the outside of the left foot into the space ahead of him. He moved to the edge of the box and then, having been negligently shown infield onto his left foot by Silvestre, curled a majestic shot into the far corner. The conception and execution of the goal were gorgeous — McManaman and Raúl touched the ball 11 times between them, covering the length of the field in the process — but United’s defending was inexplicable. Alan Hansen was wrong when he said that you can’t win anything with kids in 1995-96, but you certainly can’t win anything with this kind of childlike naivety.

'It was a stupid way to lose,' said Silvestre after the game. 'I am very disappointed. When I came on, we completely collapsed. I don't understand how it happened.' The clue, some would say, is in the question. Silvestre became a very useful player for United, particularly during the title victory of 2002-03, but his first season was a traumatic one, in which he struggled with his concentration and decision-making. There is no chance Irwin would have made such a mistake.

That left United needing three goals to qualify, and they should have got one straight away. Another of Giggs’ flicks round the corner found Keane, who muscled past Salgado and played a pass down the side for Cole, on the left of the six-yard box. He had Helguera at his back and also Casillas, who had come from his line, but managed to work a return pass to Keane, level with the penalty spot and with only Roberto Carlos on the line to beat. He sidefooted it over the bar. 'One of those nights,' said Clive Tyldesley on ITV. 'One of those nights for Roy Keane.'

For 99 per cent of the game, Keane was exceptional. His schooling with Brian Clough had made him obsessed with minutiae and detail. This, as much as anything, was the key to his greatness. Once he went onto the field, he entered a furious, almost demented concentration. 'Every football match consists of a thousand little things which, added together, amount to the final score,' Keane wrote in his autobiography. 'The manager who can’t spot the details in the forensic manner Clough could is simply bluffing.'

Keane had got the little things, the things that barely anybody notices, right throughout the tie. Yet his two most important and visible contributions had gone spectacularly wrong. It was even crueller because of the personal context. Keane had missed the previous year’s final due to suspension and, even though United would not have been in that final without his legendary performance in the semi-final against Juventus, he says he does not regard himself as a Champions League winner. In 1999-2000, he seemed on a one-man mission to win the trophy. Six of his 12 goals that season came in the Champions League, yet his failure to add a seventh all but ended United’s hopes.

Whatever chance remained had gone seconds later, when Redondo created the third for Raúl with an astonishing piece of skill. He ran 40 yards down the left and then, while facing the touchline, backheeled the ball between the nonplussed Berg’s legs before running on to collect it by the touchline and squaring for Raúl to tap gleefully into an open net. The goal is rightly remembered as Redondo’s, but Raúl’s part should not be underestimated. He made Redondo’s pass an easy one with an angled sprint away from the United defence, who had all been drawn towards the near post by Redondo. All the while Raúl was waving his hands with the desperation of a man who had seen something nobody else had seen.

On a night when both sides had enjoyed spells of extreme excellence, that goal, and particularly Redondo’s part in it, had the devastating finality of a perfect putdown. It is the moment for which Redondo’s performance is inevitably remembered, even if — to return to Keane’s detail — his more important contribution was a defensive one. 'Redondo must have a magnet in his pants,' said Ferguson. 'He was fantastic, unbelievable. He had one of those games. Every time we attacked and the ball came out of their box, it fell at his feet. Every time!' Redondo’s primary job was to carry water, albeit more gracefully than most, but here he walked on it.

Redondo has a case for being the most underrated player of all time, a balletic mover who was described as 'tactically perfect' by the exacting Fabio Capello and had the rare ability to change the pulse of a contest almost as he pleased. Yet he was excluded from Pelé’s list of the 100 greatest living footballers and also World Soccer’s list of the 100 greatest players of the 20th century. He only ever received three votes for the Ballon d’Or, all in 2000, and won just 29 caps for Argentina for a variety of reasons, including injury, a clash of philosophies and even a refusal to cut his hair.

After Redondo’s masterpiece, United staggered around dazed for a few minutes. The only bad tackle came after an hour, when Scholes was booked for bulldozing through Sávio. That moment aside, the entire tie was played in a Corinthian spirit. Real did not commit a single foul in the first half at Old Trafford. Both sides simply wanted to get down to business and try to win the game.

It came during a brief golden age of European football, culminating in the exceptional Euro 2000. In the Sunday Telegraph four days later, Gary Lineker hailed 'the top-level European game's emergence from a period of defensiveness. The most successful sides are those who show adventure, who use the talents of special players to unlock the opposition. That can only be good for the game.'

The health of a tournament can often be judged by the number of goals at the sharp end. In 1999-2000 there were 44 goals in the 13 matches from the quarter-finals, the highest between 1963-64 and 2017-18. And the total of 85 goals at Euro 2000 is a record for a 16-team tournament.

Goals were so commonplace that, even with four needed, United’s body language suggested they thought it was doable. 'I always felt we were still in it,' said Teddy Sheringham. 'It was one of those strange matches when every time they had a shot, we had a shot. It's just that they scored and we didn't. It was like a five-a-side game which is why, even at 3-0 down, I honestly thought we still had a chance.'

Sheringham and Ole Gunnar Solskjær came on for Cole and Berg just after the hour, with United switching to a 3-4-3 formation, and a goal came almost immediately. Not that it had anything to do with the substitutes: Giggs, Keane and Scholes combined to find the previously anonymous Beckham, who zig-zagged past Roberto Carlos and Sávio before shifting the ball to the side of Karanka and smacking a beautiful shot across Casillas and into the top of the net.

It was an exceptional goal and one that, according to Barclay, 'made nonsense of the myopic idea that he be restricted to the flank.' Beckham had made a goal for Cole at Middlesbrough nine days earlier with a similar run, and around this time there was a bit of a clamour for him to play in the middle for England. It always seemed pointlessly counter-intuitive — if you have the best crosser of a ball in the world, perhaps in history, why take him away from the flank? — but Beckham had been a central midfielder in his youth and was desperate to be one again. Kevin Keegan experimented thus in a friendly in France in September 2000, but he resigned a month later and the thrilling emergence of Steven Gerrard alongside Scholes meant that Sven-Göran Eriksson did not see Beckham as a regular central-midfield option until the quarterback experiment of 2005.

After Beckham’s goal, Madrid camped extremely deep and rationed their attacks. Although United had much more possession, they did not create anywhere near as many chances as in the first half. Solskjær slipped in the box, Scholes dragged a 20-yard shot across goal and just wide, and then Casillas made another fine save to deny Solskjær at the near post. A second goal finally came in the 89th minute, when Scholes thrashed in an unsaveable penalty following McManaman’s needless foul on Keane by the right edge of the area.

United needed two goals in injury time, something they had managed against Bayern Munich in the final a year earlier. They almost got one in the fifth second of added time, but Yorke headed straight at Casillas from six yards and that was that. For United, there was only the numbing realisation that their hopes of a dynasty had gone. For a time, the players seemed to be in denial. 'My mind refused to concentrate on the fact that we would not be in the final again,' Stam wrote in his autobiography, before describing a similar reaction from Gary Neville. '‘Have we really lost to them?’' Neville said. '‘I can’t believe we’ve been knocked out.’' The shock, Stam said, was 'sickening'.

With Chelsea losing 5-1 in Barcelona the night before, many of the British press — who had been hailing an era of English dominance a month earlier — denounced the English teams as football illiterates. Del Bosque’s comments about United’s tactical anarchy gave them more ammunition. 'The smug assumption of English club superiority which had wafted through the more Anglocentric sections of the media this past month,’ ' wrote Jim White in the Daily Telegraph, ‘has proved sadly hollow.’

In the same paper two days after the match, Stam rejected the idea that Real had humiliated United. ‘Some have suggested that Madrid outclassed us at Old Trafford,’ he said, ‘but I'm not having that.’ He told Solskjær that he wanted to play the match again. Ferguson also said he thought United would win the match seven times out of ten. ‘Though the glib consensus was that United had been easily outsmarted by a better side, the reality is more nuanced,’ said Daniel Harris, author of The Promised Land: United’s Historic Treble. ‘But for their Bernabéu timidity, things might have been very different. Instead, the aura was gone forever.’

And Real’s was on the way back. Although they won the Champions League in 1998, they had been a relatively dowdy club for much of the previous decade. They had won just two of the previous nine titles, their worst run since the 1950s, but they drew inspiration from the win at Old Trafford and comfortably beat Bayern Munich and Valencia to lift the Champions League. That gave them the clout to steal Luís Figo from Barcelona in 2000 and begin an era of brazen galácticism which, though ultimately unsuccessful, restored their place as the most glamorous club in the world. Had Real not ludicrously got rid of both Del Bosque and Claude Makélélé — a man who, like Jeffrey Lebowski’s rug, really tied the room together — in 2003, the galáctico experiment would probably have been a success.

Those galácticos had won another Champions League under Del Bosque a year earlier, making it three in five years. No other club had dominated the tournament to such an extent since its inception in 1992, although this wasn’t a dynasty as such. Each side had different identities. Only four of the team that started the 1998 final also began the 2000 final, and only five of that XI started two years later.

The biggest impact of this match came at Old Trafford. It punctured United’s self-belief and made Ferguson investigate alternative tactical options. ‘One of the forceful reminders delivered by that defeat,’ he said, ‘was that consistent success in Europe would be more readily achieved if we improved our capacity to defend against the counter-attack.’ From then on, Ferguson decided that, with destruction intrinsically more controllable than creation, it made sense to prioritise the former.

His attitude was shared by Arrigo Sacchi. ‘Manchester are a very good side,’ he said after the game. ‘But their win last season was exceptional. Madrid, I believe, are more likely to win the Champions League on a regular basis. Their style of play, alone, means they are better equipped to dominate Europe.’

‘You can't keep giving yourselves mountains to climb, especially against the top teams,’ said Keane after the game. ‘But it is the way we play and I think it will be hard for us to change.’ So it proved. This great United side would not win multiple European Cup knockout games, let alone European Cups; their win over Deportivo in 2001-02 was their only victory in a knockout tie between 1999 and 2007.

In 2000-01 Ferguson kept the same personnel and system, but United were much cagier in Europe. Then, in the summer of 2001, he bought Juan Sebastian Verón to play in a 4-2-3-1 system, with Scholes behind Ruud van Nistelrooy and able to drop into midfield when United did not have the ball. In the short term, the move was a disaster: by breaking up the midfield of Beckham-Keane-Scholes-Giggs, Ferguson killed a golden goose that was delivering a Premier League every season. Nor did it lead to an improvement in Europe.

Ferguson, who originally planned to retire in 2002, could not have imagined that even such a fundamental change could be this problematic. When United were eliminated in the group stages of the Champions League in 2005-06, most assumed he was finished. Even McIlvanney, in his Sunday Times column, said that ‘eventually there comes a moment when the best and bravest of fighters shouldn’t answer the bell.’ Yet Ferguson’s obscene resilience drove United to three consecutive titles between 2006 and 2008 and, best of all, another European Cup in 2008. He also — finally — managed to fight off the away goal. Having failed to keep a clean sheet in nine consecutive knockout matches from 1998 to 2007, United then did so in six of the next seven. They were tactical pioneers, with a 4-3-3-0 system that was the envy of Europe, and became the first United side to reach four European semi-finals in five seasons.

Many still feel Ferguson would have won more European Cups by sticking to a fearless 4-4-2. It’s impossible to know, but what is fascinating is that he ripped up his system based on such an unusual game. This was not the type of straightforward match from which easy conclusions can be drawn, unlike, say, United’s quarter-final a year later, when they were quietly but emphatically thrashed 3-1 on aggregate by Bayern Munich.

The Real Madrid match has a million different interpretations, and umpteen unusual elements. There was Ferguson’s description of Casillas’s performance as ‘not normal at all’. There was his feeling that ‘just about everything that could possibly go wrong for us did so in spades, and we were left looking back on the match with the sense that Real were simply destined to progress into the semi-finals.’ There was also Redondo’s superhuman display, the fact that United’s defence was unusually hapless that season, the improbability of Keane scoring an own goal, the fact that Yorke, so vital the previous season, had lost his way. There was the post-Treble loss of hunger discussed by Keane, who in those days was generally seen to be his master’s voice. Then there was something perfectly normal: the fact that you are allowed to lose a game of football to Real Madrid.

Despite all this, Ferguson decided to rip it up and start again. It’s a fascinating snapshot of a man blessed with the courage necessary to take risky and brave decisions, from dropping Jim Leighton for the 1990 FA Cup final replay to selling Paul Ince, Mark Hughes and Andrei Kanchelskis in 1995. ‘His ruthlessness and clear-sightedness (at least in seeing what was wrong, if not necessarily what the solution was), is precisely what makes him a genius,’ wrote Jonathan Wilson. ‘It is one thing to build a great side; quite another to be brave enough to dismantle it and start again, shaping football’s evolution even as you adapt to its changing shape.’

The other decision Ferguson took was to compromise the traditions of Manchester United. The pursuit of glory and the commitment to attacking football were woven into the fabric of the club by Sir Matt Busby. Ferguson’s caution in Europe soon extended to big games domestically, and the number of vital matches in his last few years in which United attacked from the start can be counted on the fingers of one hand. The most extreme manifestation came at the Nou Camp in 2008, when, despite having Cristiano Ronaldo, Carlos Tévez, Wayne Rooney, Michael Carrick, Owen Hargraves, Park Ji-Sung and Scholes on the pitch, United packed men behind the ball and had only 28 per cent possession.

They drew that game 0-0, as they had in Madrid, but this time got through with a 1-0 win in the second leg and went on to win the competition. Scholes’ memorable goal was one of only three shots on target that United had in the entire tie, and the debate endures as to whether such an approach was acceptable. Ferguson tried something similar in a mustn’t-lose game at the Etihad in April 2012. This time United lost 1-0, without having a shot on target, and City went on to win their first title since 1967-68.

Would Ferguson have won more European Cups without such a dramatic change? Nobody knows. But the long-term impact of that Madrid tie imbues a comment made by Steve McClaren a month earlier with a certain poignancy. ‘While you are top of the pile,’ he said, ‘it is very, very important to continue winning and then you will become one of the legendary sides. That means winning the European Cup two, three, four out of five years. The players want to do that. They are a great team, but I believe they can be so much better and become one of the all-time legendary teams.'

They didn’t quite manage it, largely because of an underrated contest that — in its excellence, complexity and magnitude — was like no other in European history.