Manchester United 3-0 Barcelona (agg: 3-2), Cup Winners’ Cup quarter-final second leg, Old Trafford, 21 March 1984

Matt Busby and Alex Ferguson brought glory and trophies to United on an industrial scale, yet they never had an Old Trafford European night like this. Ron Atkinson’s cup specialists overcame a 2-0 first-leg defeat to overwhelm a Barcelona side that included Diego Maradona and Bernd Schuster. United’s three goals, two from Bryan Robson and one from Frank Stapleton, were scored from a combined distance of around six yards, an apt reflection of a night on which they stormed the Barcelona goal like it was a medieval fortress. Barcelona, used to a slower pace domestically, simply could not cope with United’s tempo.

The last of the goals came in the 53rd minute, which led to nerves being Freddy Kreugered for the remainder of the match, and Mark Hughes was lucky not to give away a penalty late on for a clumsy lunge at Gerardo. ‘I thought we took the third goal too early,’ said Atkinson after the game. ‘The last quarter of an hour felt like about three days.’

His players put in some immense performances – particularly the 19-year-old Graeme Hogg, who had scored an own goal in the first leg, and Remi Moses. Between them, they harassed Maradona into anonymity. But all anyone ever talks about is Robson’s display, which cemented his status as the most irreplaceable player in English football. When Elton Welsby collared him in the tunnel for a Granada TV interview, after he had been carried off by adoring United fans, Robson was so exhausted he could barely speak.

Nobody else had any trouble making noise. Everyone involved says the atmosphere has never been repeated at Old Trafford. Legend has it there were complaints about the noise as far away as Rochdale.

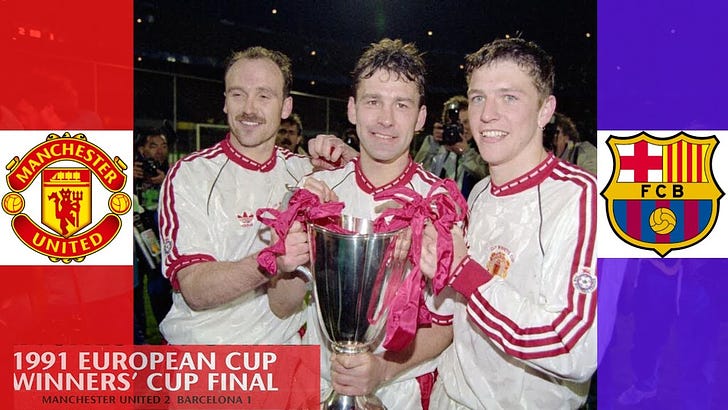

Manchester United 2-1 Barcelona, Cup Winners’ Cup final, Rotterdam, 15 May 1991

Bryan Robson agrees that his best performance for United was against Barcelona – but he’s not talking about 1984. He takes the greatest pride in a more subtle display in the 1991 Cup Winners’ Cup final, when he controlled the midfield as United won their first European trophy in 23 years.

The recurring theme of Alex Ferguson’s matches against Barcelona was his obsession with the centre of midfield, where all Barcelona teams since Cruyff’s have tended to outnumber and outclass their opponents. At the age of 34, Robson – who was really hurt by being dropped from Graham Taylor’s England squad - produced an unshowy but near flawless display of positioning, tackling and passing.

He also created both of Mark Hughes’ goals. The first was stolen on the line from Steve Bruce’s header; the second, battered in from a prohibitive angle with both feet off the ground, was straight out of a comic book. For Hughes, it provided the purest catharsis after his miserable spell at Barcelona.

At a time when tactics was a swearword in English football, the match was an early example of Ferguson’s love of a good chalkboard. He asked Brian McClair to drop onto Ronald Koeman when United lost the ball, to stop Barcelona’s passing carousel at source, and a technically inferior United – this was pretty much the same Barcelona team that won the European Cup a year later – were deserved winners of a scruffy game despite a jittery spell after Les Sealey’s late own goal.

Cruyff reacted as you might expect to the sight of his 3-1-2-3-1 formation being trumped by 4-4-2 . ‘They had one more chance than us - I don't think they were superior,’ he said, elevating his nose at an angle of precisely 45 degrees. ‘United played the British game.’ Ferguson, and especially Robson, would have taken that last sentence as a compliment.

Barcelona 4-0 Manchester United, Champions League Group A, Nou Camp, 2 November 1994

‘Manchester United are about to find out how good they really are, in front of 110,000 witnesses.’ The opening line of David Lacey’s match preview in The Guardian is so perfect that it feels as if it was filed from the future. Alex Ferguson found out that his first great United team were a million miles short of succeeding in the European Cup, and not only because of the pesky foreigner rule that led to the almost shocking omission of Peter Schmeichel for this game.

To channel Martin Johnson, that United team had only two problems in Europe: getting the ball and keeping it. They were top of their group when they travelled to Barcelona, having drawn 2-2 in a thrilling return game a fortnight earlier, but what followed was one long intravenous injection of reality. In what turned out to be the last hurrah of Johan Cruyff’s Dream Team, Romario and Hristo Stoichkov left United’s centre-halves Steve Bruce and Gary Pallister with twisted everything. ‘I had,’ said Bruce, ‘an absolute beast.’

Just about the only attack Bruce managed to stop was in the dressing-room at half-time, when he and Brian Kidd prevented Ferguson and Paul Ince taking their relationship to the next level, and not in a good way.

It started when Ferguson blamed Ince for United being overrun in midfield.

You’re a fucking bottler, Incey! You can’t handle the stage, can you?!

Don’t you dare call me a bottler, gaffer! Don’t you dare!

At that point Ferguson walked purposefully over to Ince and hissed in his face: ‘You. Are a fucking bottler!’

It was the beginning of the end of Ince’s United career. Fairly or not, Ferguson saw him as a big-time Charlie and a big-game bottler.

United, used to 100-miles-an-hour football, could not cope with the sudden change in tempo of Barcelona’s attacks. You could write a book on the genius of Romario, and we wish someone would, but it’s notable that Pallister picked out one quality above all others. It wasn’t his finishing, his movement or his speed from a standing start. It wasn’t even his persecution of United defenders called Gary. The thing that struck Pallister the most was Romario’s awareness. He was always looking over his shoulder to see where Pallister was, reversing the usual relationship between forward and defender, before slithering into a position where he could expose Pallister’s high centre of gravity.

‘Pallister and Bruce were both auditioning for the role of Juliet: Romario, Romario, wherefore art thou Romario?’ wrote Lacey in his match report. ‘And nobody had a clue about Stoichkov’s whereabouts.’ Pallister was a majestic centre-half in English football; this was the one time in his career when he walked off the pitch knowing he’d been out of his depth. In a dark corner of his subconscious, Romario owns a 99-year lease.

Barcelona 3-3 Manchester United, Champions League Group D, Nou Camp, 25 November 1998

The treble season had such a perfect killer-filler ratio that the two astonishing 3-3 draws against Barcelona in the Champions League group stage are a pair of great songs tossed off as B-sides. The second of those matches, which Louis van Gaal’s Barcelona had to win to stay in their tournament (the final, as you may have heard, was to be played at the Nou Camp), had almost as much in common with basketball as football. For both sides, valour was the better part of discretion. ‘It was a night of complete abandon,’ said Alex Ferguson, ‘played exactly in the spirit of “let the best team win”.’

Two memories in particular stand out: Dwight Yorke and Andy Cole taking their relationship to another level with a Zorroish swish through Barcelona’s defence, and the demented magnificence of Rivaldo’s attempts to keep Barcelona in the tournament. He scored two superb equalisers, lasered a shot onto the crossbar from 30 yards and brilliantly created a late chance for Giovanni that was saved by Peter Schmeichel. Few footballers have ever failed quite so gloriously.

Manchester United 1-0 Barcelona (agg: 1-0), Champions League semi-final, Old Trafford, 29 April 2008

The greatest trick Carlos Queiroz ever pulled at Old Trafford was to get out some gym mats. When United played Barcelona in the 2008 semi-finals, Queiroz andAlex Ferguson were so determined to restrict Barcelona’s ‘passing carousel’– a phrase Ferguson coined before the second leg – that they went through an unprecedented level of tactical preparation.

During training, Queiroz placed gym mats between the two midfielders, Michael Carrick and Paul Scholes, and the two defenders, Rio Ferdinand and Wes Brown (with Nemanja Vidic injured, Brown had the tie of his life). The ball was not allowed to touch the mats in any circumstances, and Queiroz walked the four players through exactly where they should be in relation to the ball.

It worked: United restricted Barcelona to few chances and no goals across the two ties, and reached their first Champions League final since 1999 thanks to Scholes’ howitzer on a brain-melting night at Old Trafford. It was probably, across both legs, their most negative performance in Ferguson’s 26 years at the club, but the end justified the means. And the mats.

Barcelona 2-0 Manchester United, Champions League final, Rome, 27 May 2009

The Champions League finals of 2009 and 2011 are often presented as a duology. That’s understandable given the recurring majesty of Andres Iniesta, Xavi and Lionel Messi, and the sight of United being reduced to numbing impotence. Yet whereas the 2011 final was as close to unwinnable as dammit, 2009 was different – a game in which, though they were ultimately outplayed, United went away asking life’s cruellest question: what if?

What if they had scored during their blistering start? What if they hadn’t given away such a soft goal to Samuel Eto’o when they were completely on top? What if the irreplaceable Darren Fletcher had not been suspended after a dubious red card in the semi-final at Arsenal? What if they had picked a better hotel? Many have ridiculed Ferguson for that last one, particularly those who have not once used a bad hotel as an excuse for a defeat on Champioonship Manager, but 18 years earlier he cited the quality of their hotel and preparation in Rotterdam as a major reason for the Cup Winners’ Cup final defeat of Barcelona.

Pity poor Michael Carrick, who was left to deal with the greatest midfield in football history of his own because of errant performances by Anderson (2009) and Ryan Giggs (2009 and 2011). He had to cope with Xavi and Iniesta, which was like confronting a superior version of himself - only there were two of them, and they also had support from Messi. ‘It was as if they owned the ball,’ said Carrick, ‘and were playing their own private game.’ Everything needs an acronym or an abbreviation these days: Messi, Iniesta and Xavi were the little mix who proved size doesn’t always matter.

Carrick played the 2009 final with a broken toe and says he has ‘never got over’ his imprecise header near the halfway line that ultimately led to Eto’o’s goal. That game had such an impact that he struggled mentally for the next two years. He found it much easier to deal with 2011, because by then Barcelona were in a different stratosphere. But he, and United, will always wonder about 2009.

Barcelona 3-0 Manchester United (agg: 4-0), Champions League quarter-final, Nou Camp, 16 April 2019

Do we have to?

An earlier version of this piece appeared in the Guardian in 2019.